Clinical Trials of Brain-Computer Interface Show Long-Term Safety Results

Synchron, a U.S.-based medical technology company with offices in Melbourne, Australia, published their clinical study on the effect of implantable brain-computer interface on paralyzed patients. All four participants of the study effectively sent neural signals.

The company’s study emphasized the clinical study’s long-term safety results, where they implanted their first-generation Stentrode into four severely paralyzed patients. With their neuroprosthesis device, the four patients successfully controlled a computer.

The excellent results that Synchron achieved indicate that it is possible and safe to use the neuroprosthesis device. The device, which doctors place inside a blood vessel in the brain, helps the patients’ long-term transmission of neural signals with no serious side effects.

Synchron’s SWITCH study

The study, which they call SWITCH or With Thought-Controlled Digital Switch, Synchton’s research symbolizes the first-in-human study of its kind. They conducted the study for 12 months on the four paralyzed patients they implanted with Stentrode developed by Synchron.

During the research period, the patients did not develop clots. Moreover, the implanted device did not move from its original position. The signal quality was stable, and there was so sign of deterioration.

Aside from the stability of the device, the researchers were impressed by the performance of the four participants. They consistently controlled a personal computing device using the brain-computer interface. Thus, they ably performed several actions, such as emailing, texting, online shopping, personal finance, and communication if they needed care.

Their typing speed was about 14 characters per minute hands-free and without using any predictive text technology, and they achieved 90 percent accuracy in cursor clicks using the system,

Overall, the participants could reach typing speeds of at least 14 characters per minute without the help of predictive text technology. They also achieved more than 90% accuracy in controlling cursor clicks through the system.

Synchron said they conducted the study’s procedures on a neuro-interventional angiography suite because it was the first-in-human study, and they prioritized safety. According to the researchers, the participants tolerated the procedure (implantation of the device) well and were sent home within 48 hours. The company conducted the first-in-human study at the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

The Synchron interface

Paralysis causes the loss of control of the body’s muscles. But the motor intent typically remains active in a paralyzed patient’s brain. So despite the paralysis, it can still incite the physical will of the person to move.

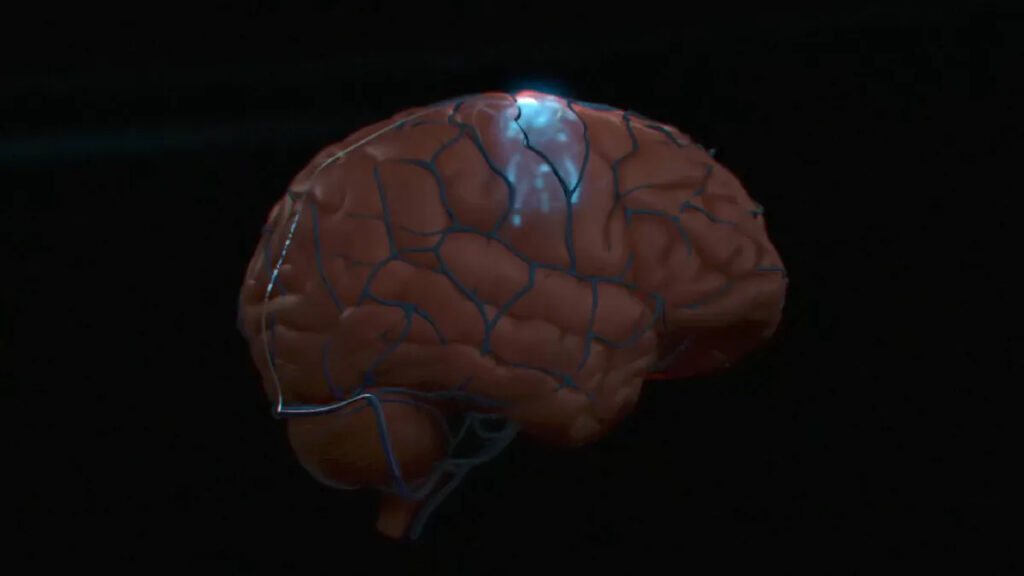

Synchron engineered its brain-computer interface to restore the lost motor intent signal transmission caused by paralysis. They surgically place the device into the brain’s motor cortex by passing it through the jugular vein.

The surgical procedure is minimally invasive. After the implantation of the device, it immediately detects moving on to transmit motor intent wirelessly. This is how the brain communicates, allowing the wearer of the device to control the digital devices they use.

A vascular neurologist from the Royal Melbourne Hospital and the University of Melbourne, Professor Bruce Campbell, commented that the Stentrode technology is promising for paralyzed people who wish for independence. It can enable a form of motor restoration where patients can use switches to communicate and engage digitally.

The researchers say their SWITCH study provides an early demonstration of safely employing a commercial-grade brain-computer interface.

After the success of the SWITCH study in Australia, the U.S. is next to conduct the clinical trial. The surgical implantation occurred in January 2023 at the Mount Sinai Wes Hospital in New York City. The FDA authorized the study. Five more patients will receive the Stentrode soon.